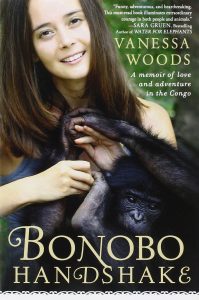

The Potential of Female Leadership explores what lessons we may learn from bonobos’ matriarchal social structure, so we can build stronger, more collaborative human communities and groups. Bonobo Handshake is an enthralling insightful book, which I review here. A tremendous bonus is its similarities to and significant differences from Chimpanzee Politics (reviewed yesterday).

The Potential of Female Leadership explores what lessons we may learn from bonobos’ matriarchal social structure, so we can build stronger, more collaborative human communities and groups. Bonobo Handshake is an enthralling insightful book, which I review here. A tremendous bonus is its similarities to and significant differences from Chimpanzee Politics (reviewed yesterday).

Bonobo Handshake was on the same library shelf as Chimpanzee Politics, but it is a very different book, and in delightful ways. At the same time, it offers intriguing insight into bonobos’ behavior, which differs significantly from chimpanzees’ and holds interesting lessons for human societies and groups. Although Woods is not a primatologist per se, she has conducted extensive research with her husband, who is, so explaining scientific experiments forms a key part of this book.

Bonobo Handshake is rare in a surprising way. Deftly and subtly, it contrasts the joy, harmony and matriarchal structure of the bonobos with chimpanzees’ and humans’ patriarchal societies and violence: the wars in and around the two Congos result in the murder of chimpanzees and bonobos because people hunt them for food, and humans have been murdered and women raped en masse for years now. I felt that Woods did this without judgment, almost like her curiosity and the juxtaposition of events produced the contrast spontaneously. So the book is a story within a story.

Overview

Bonobo Handshake is a “memoir” of Woods’ journey of finding her life’s work, studying primates: meeting Brian Hare by accident, conducting research with him in DRC (Democratic Republic of the Congo) and RC (Republic of the Congo), and facing life and death situations (horrible wars in and around these countries). So it reads like a novel.

Bonobos are a rare breed of primate that lives in matriarchies, so studying their behavior enables us to question some assumptions about human behavior, namely what is the fundamental nature and impact of female-dominated leadership?

The Book

Bonobo Handshake is essentially a narrative, so it’s otherwise unstructured, but Woods is an engaging writer, so the book is a page-turner. Rather than discuss its structure, here are some of its themes, roughly in the order of their appearance:

It’s a finding herself story. Woods had spent most of her twenties bouncing around the world doing research on primates, writing and shooting videos. Then a chimp, Baluku, changed her life. She was working in a sanctuary (an orphanage) in Uganda and became Baluku’s “surrogate mother” (like human babies, chimps and bonobos spend their first years clinging to their mothers, so human females become surrogates to infants and babies).

“It was the first time I had to give myself so completely. But I didn’t feel trapped or resentful because I never had a moment’s rest or a solid night’s sleep. Baluku’s love was its own reward.”

It’s a love story. Her master’s is in “science writing,” so serendipitously meeting Hare, who was also passionate about studying (and helping) chimps, enabled Woods to take her own love for primates to a different level. She’s very entertaining with the love story part, and she includes delightful parallels between her love and life experience to chimps’ and bonobos’ behavior, but seemingly unintentionally, which I found delightful. And their story unfolds in Germany, the U.S.A. and in several African countries.

It’s a primate story. Both Woods and Hare had focused on chimps when the story starts, and Hare got the opportunity to study bonobos almost accidentally. Moreover, bonobos challenged their research methods to the core because key assumptions failed. For example, chimps will do anything for food, so they are pretty easy to reward, a key element of experiments. Bonobos are more blasé about food, and less easy to predict. Hare and Woods discovered that bonobos use sex for recreation and (they think) to defuse social tension. So “bonobo handshake” is touching a bonobo’s genitals. They masturbate and rub each other’s genitals a lot and have sex in the “missionary position” most of the time, whether for social value or procreation. So Hare and Woods had to hack different research procedures to study bonobos. This was even more challenging because many of their experiments compared behavior of chimps to bonobos’. In addition, bonobos strongly prefer human females, so that limited Hare’s roles within experiments in unexpected ways. They are not easy to study using a chimp paradigm!

It’s a war story. Woods was horrified when Hare had to change their plans: based in Germany at the opening of the book, they’d intended to go to Uganda to study chimps, but opportunity took them to DRC to study bonobos instead, so Congo’s bloody war menaced them at every turn. This was personally challenging for Woods, whose father had fought in the Vietnam War and had returned home with severe PTSD, and she’d been estranged from him for many years. She recounts many anecdotes about disfigured families and widespread destruction off the cuff, through relating experiences of people they worked with, so these tales are very natural. That gives the sense of just how widespread the violence and destruction are. And their lives were in danger several times. She includes a fair amount of the history, events and drivers of the wars, too.

In summary, if you are interested in human behavior, which is primate behavior through and through, this book is a must-read. It’s such a subtle and surprising cocktail of numerous contrasts: love and war, bonobo-chimpanzee-human behavior, matriarchy and patriarchy. All while being immensely entertaining and quite humorous.

I also found it deeply moving and meaningful because bonobos are endangered, and many people are dedicated to saving them. By extension, it carries a powerful warning that, unless we learn to modulate our competitive, exploitative and destructive nature better, we will destroy the world (and everything in it). This book shows that there are very different ways to be primates: chimpanzees are more similar to humans in their competitiveness, and bonobos offer alternative behaviors. Woods’ stories of humans’ interactions with bonobos, and bonobos’ interactions with each other, effectively blur the boundaries between the species: bonobos are so “human” that I found myself losing my frame of reference a few times.

Conclusions

- According to our (human) perception, we have the most choice of any animal in how to “be” ourselves. Theoretically, we can use our conscious minds to make choices that go against our nature, which unequivocally seems to be competitive and to exhibit strong “us and them” thinking. Hare and Woods theorize that bonobos’ matriarchy stems from plentiful food in their natural habitats. Where chimps have to forage far and wide to find food, bonobos pick plentiful fruit off trees, lounge around and socialize. There are very few matriarchies in nature.

- Bonobos are more collaborative than chimps, during experiments and in the wild. So what can we learn about female leadership that could help us become more collaborative and less aggressive and exploitative? We are in danger of destroying bonobos’ natural habitat before learning their secrets, which could benefit humans, and by extension, the whole planet since we endanger the whole thing.

- My work in experiential social media is all about studying behavior so my teams can interact in ways that build trust with people in digital public. So Hare’s and Woods’ experiment that contrasted chimps’ “us and them” behavior with bonobos’ “us and us” is fascinating and useful. Chimps are suspicious and fearful of strangers, and bonobos are not. Understanding this behavior could help me to enable my teams to create more harmony faster. The importance of trust itself is based on “us and them” behavior: “us” is trusted and accepted; “them” is mistrusted and destroyed if we have to (figuratively and literally).

- As I’ve written before, my crystal ball says that part of humans’ current crisis is the frightening recognition of the Earth’s limits. For the first time in our history, there’s no distant shore to conquer. The planet is getting smaller and smaller. There are no virgin resources to plunder. Our impact on Earth is incredible and growing. I think that, in many instances, female leadership would be more adaptive than male leadership, so studying matriarchy could enable us to understand leadership and make better choices. The animal kingdom has few examples of matriarchy.

- It is an open question whether we can use our conscious minds to countermand our core nature of competitiveness, but it is a life-and-death issue that we must face, or I think we will end up destroying the earth. Our impact on the earth has grown astronomically over the last century and our impact is increasing geometrically, if not exponentially. For Earth’s sake, I hope we can learn this in time.

- Bonobo Handshake’s website has all kinds of links to additional information, and Woods’ personal website offers links to some of Hare’s and Woods’ published articles in which they compare chimps’ and bonobos’ behavior.

- If you’re interested in the primate connection to human behavior, use this blog’s primate tag to see similar posts.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.